AlphaFold and the Science We Can Actually Do Now

When AI skips the grunt work, researchers start asking different questions

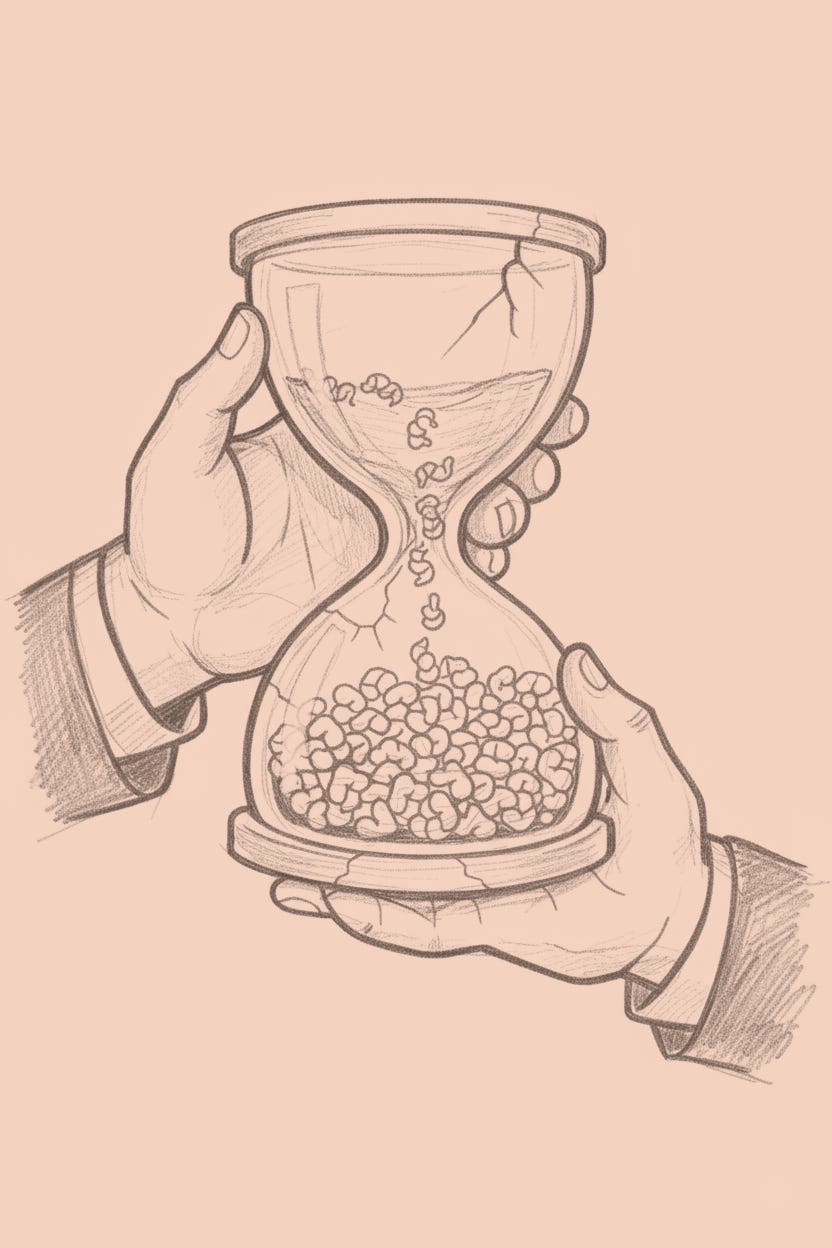

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin spent thirty years staring at insulin while the Beatles broke up, humans walked on the moon, and three generations of grad students wondered if they’d ever publish. This wasn’t failure. It was a hostage situation with physics, and we were all paying the ransom. Max Perutz spent twenty years on hemoglobin. These timescales weren’…