The Performance Economy of AI Adoption

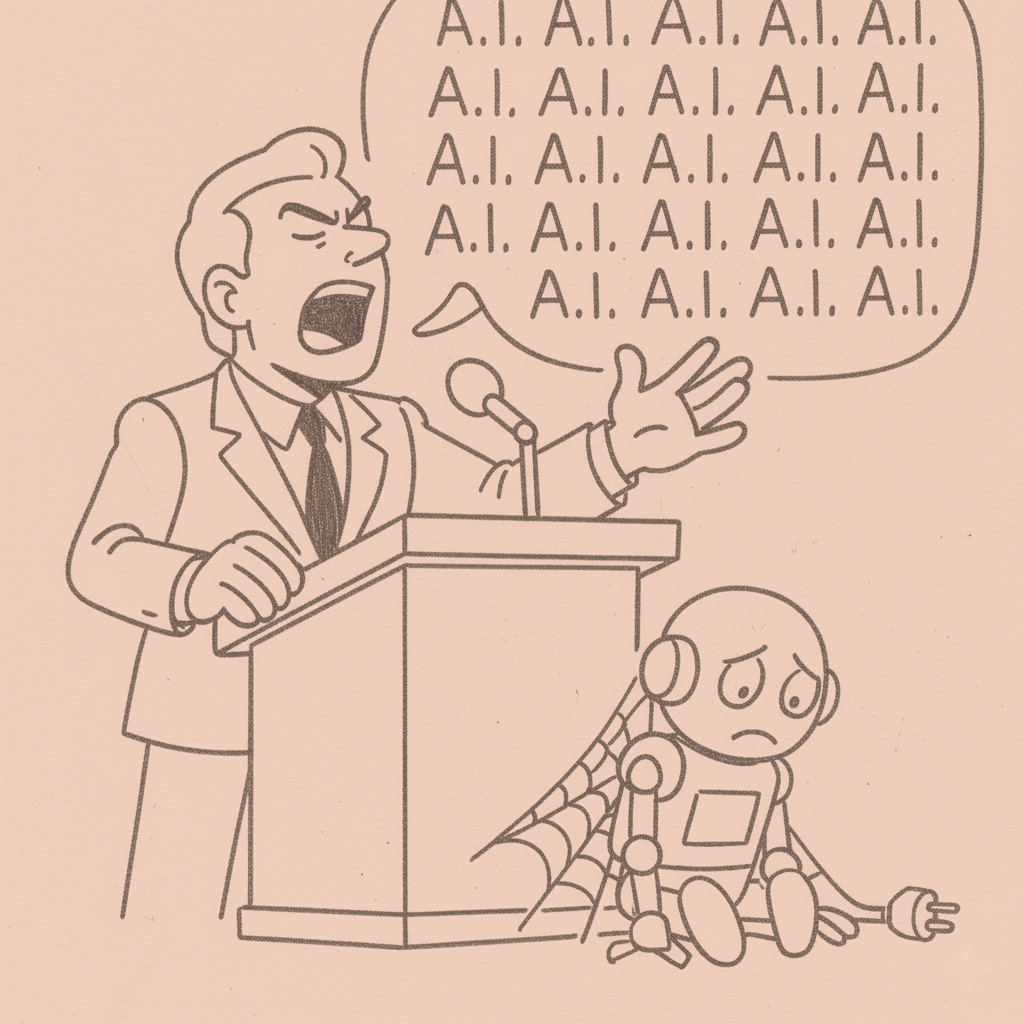

When Discussing Transformation Becomes More Valuable Than Delivering It

A Fortune 500 CFO mentioned “AI” forty-seven times in one earnings call. Their actual AI deployment? A chatbot named “Ava” that tells customers their orders are delayed. Ava delivers bad news in a voice that could read bedtime stories.

Next up: “Mom” for restructuring announcements (disappointed but loving). “Coach” for performance reviews (motivational …