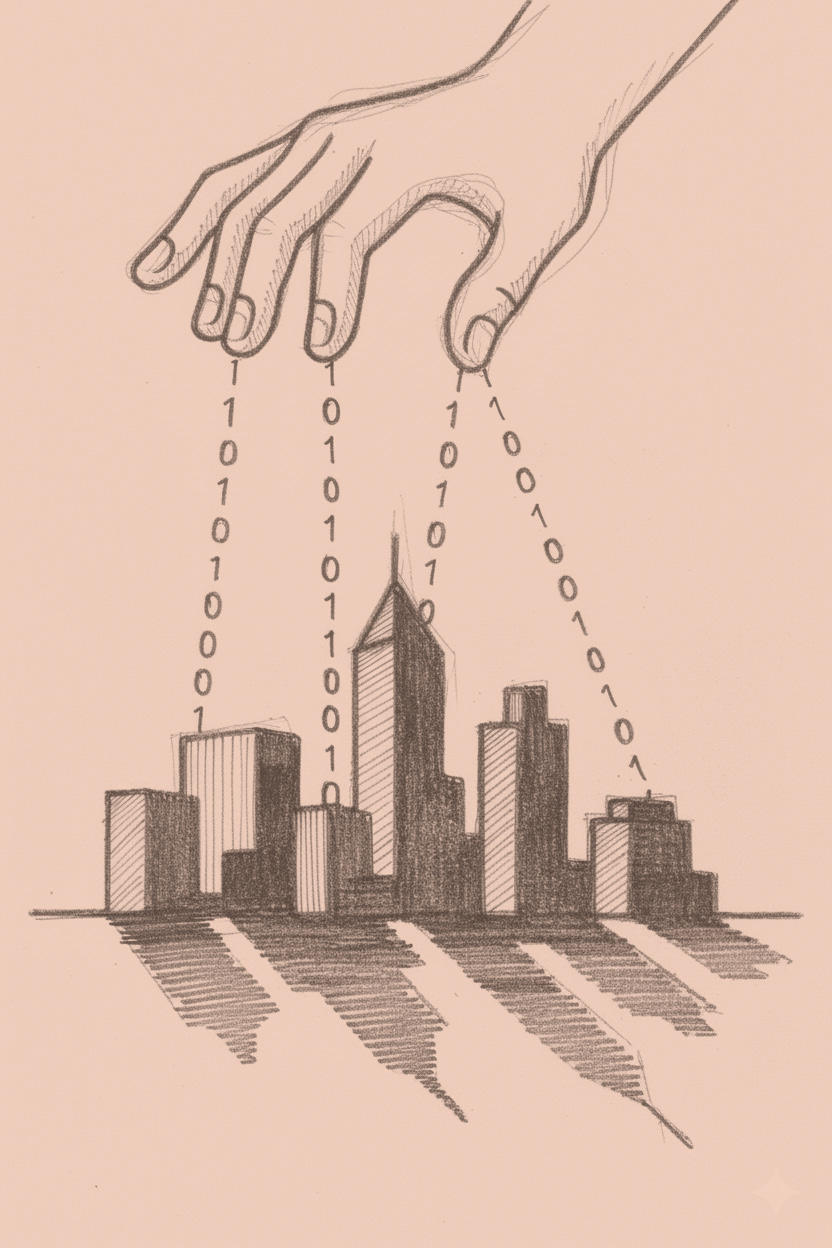

Digital Twin Cities

The simulation that runs alongside the real thing

Singapore’s ghosts are casting shadows before the living exist. Virtual sunsets illuminate walkways that haven’t been poured. Planners manipulate phantom rooflines, watching digital darkness fall across non-existent pavement. They adjust. The shadows shift. Satisfied, they test wind patterns through corridors that exist only as coordinates.

This isn’t ur…