Memory Mines

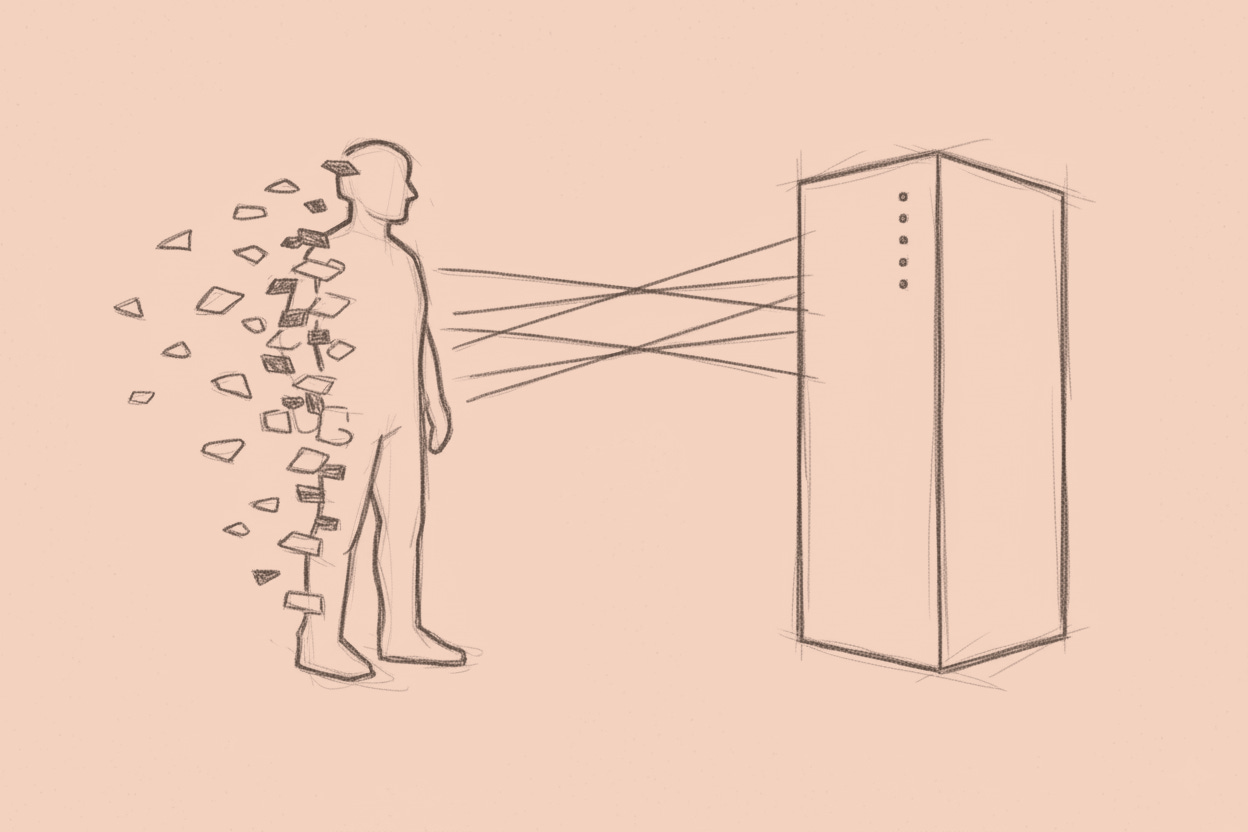

Who owns your ghost cache when the cloud remembers everything you forgot

Google remembers October 14th, 2019. You don’t.

Your phone’s location history places you at a coffee shop at 8:47 AM, a medical building at 10:23 AM (the dermatologist, not the one you’re thinking of), and a twenty-three-minute stop at an address you no longer recognize. Your email archive holds a thread about a project you’ve completely forgotten, popul…