Synthetic Flavor

The food that tastes like memory you never had

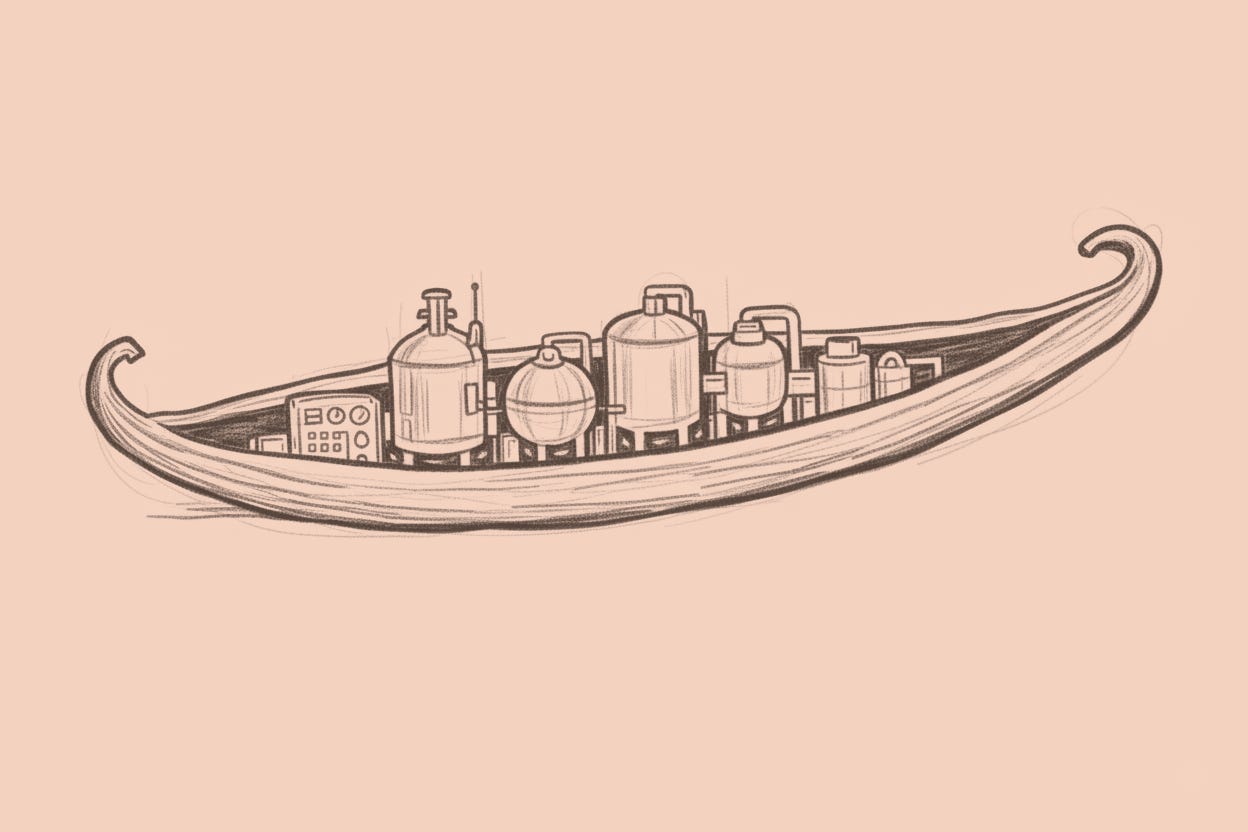

The carbon-14 test is the only thing that can tell them apart, and even that requires a lab. Synthetic vanillin and natural vanillin are molecular twins, identical down to the last hydrogen bond. Your tongue can’t tell the difference. Your brain can’t tell the difference. The distinction exists only in the story and the price tag: natural vanilla costs …