The Accessibility Revolution Nobody's Marketing

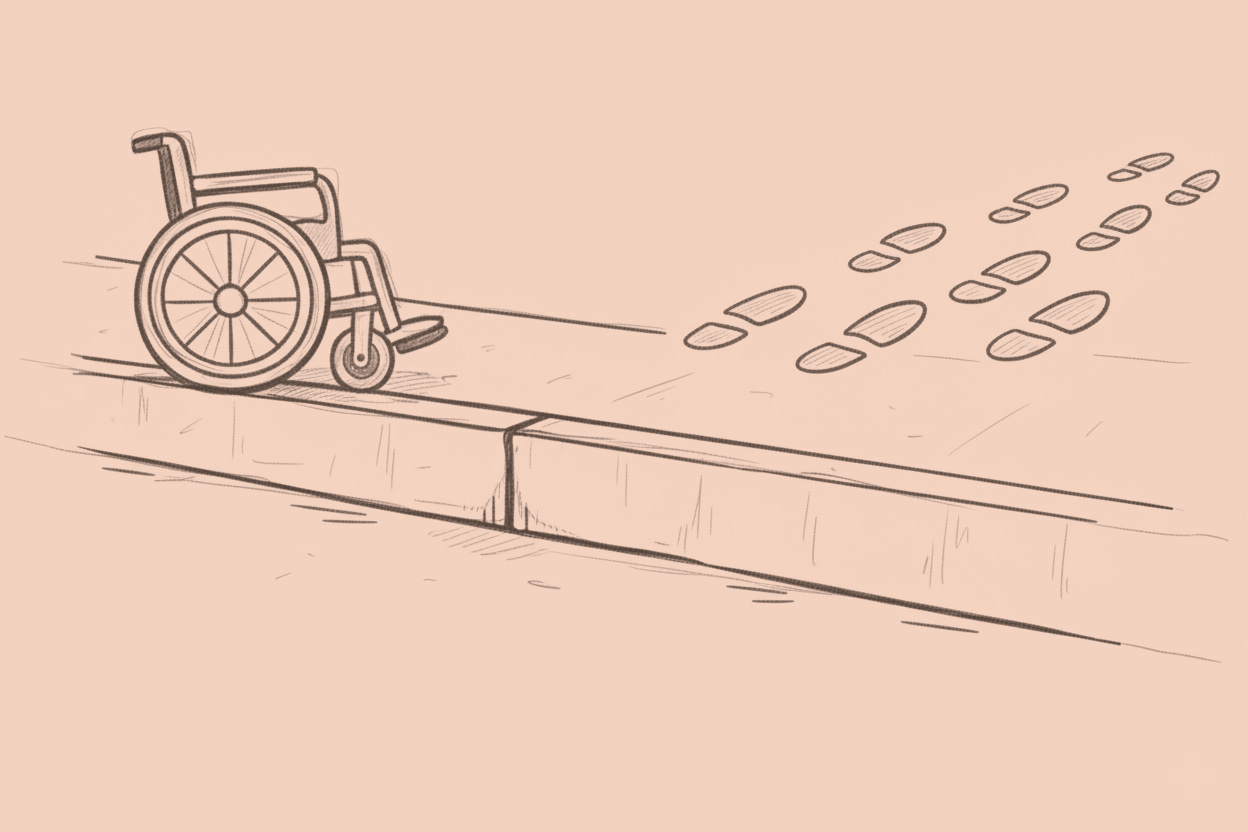

How AI tools built for disabled users reveal that 'normal' was always a polite word for exclusion

Last December, a major platform released a feature that annotates sighs.

This wasn’t transcription. It was translation of the music between the words: shouts annotated as ALL CAPS, background applause labeled, the pause before a refusal identified and logged. The AI processes the emotional subtext on-device, no server required.

It was built so deaf people…