The Dirt Nobody Photographs

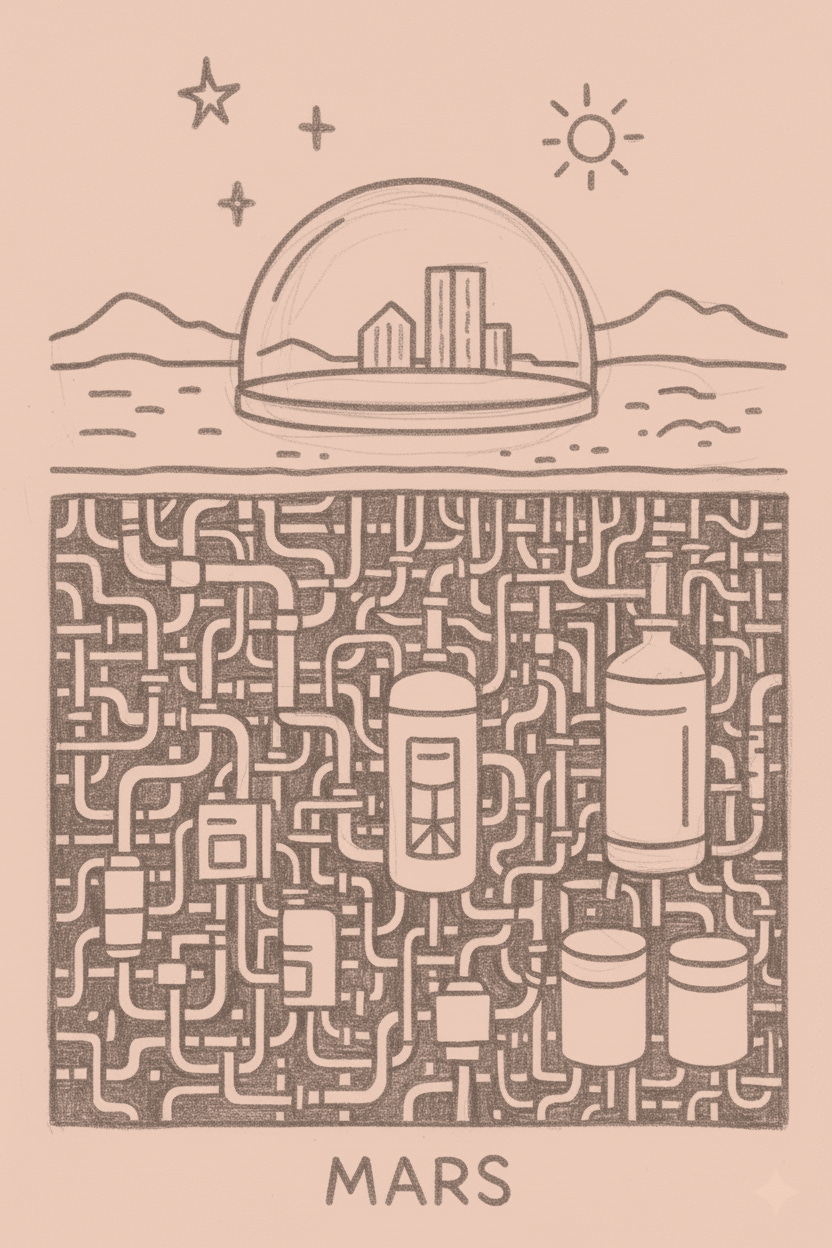

Mars settlement visions feature domes and greenhouses. The chemical warfare beneath them? Less photogenic.

We stare at Mars with familiar longing. The Martian dream has become our generation’s manifest destiny: gleaming domes under pink skies, astronauts-turned-farmers, rockets ascending like modern cathedrals. These images dominate media coverage and investor presentations with equal fervor. But beneath these romanticized renderings lies a problem nobody ph…