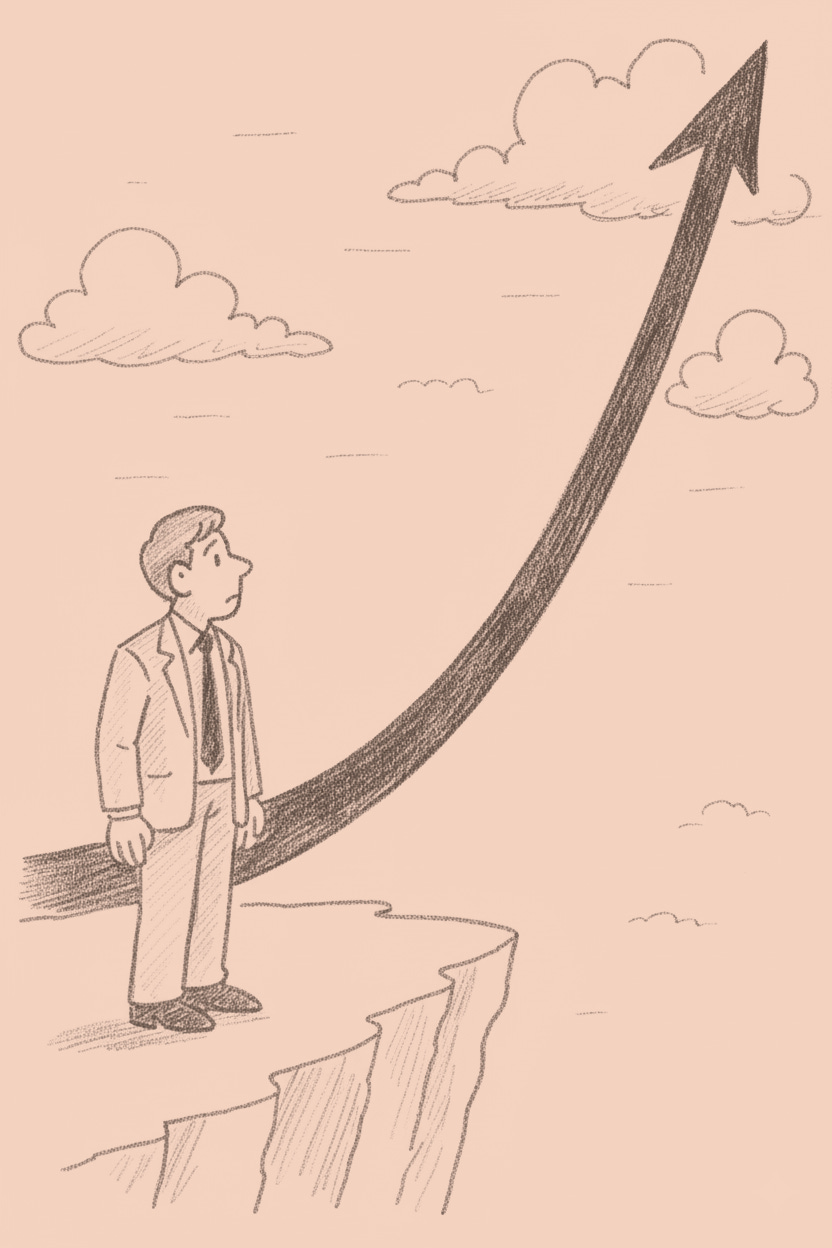

The Inevitability Reflex

What Trillion-Dollar Bets on Uncertain Outcomes Reveal About Corporate Psychology

The Question Nobody’s Asking

By the time you finish this paragraph, another million dollars will have poured into AI ventures. The surge from $3 billion in 2022 to $25.2 billion in 2023 wasn’t growth. It was combustion. Venture capitalists now control over 70% of this river of capital, each hunting for the next OpenAI like it’s the last escape pod on a b…