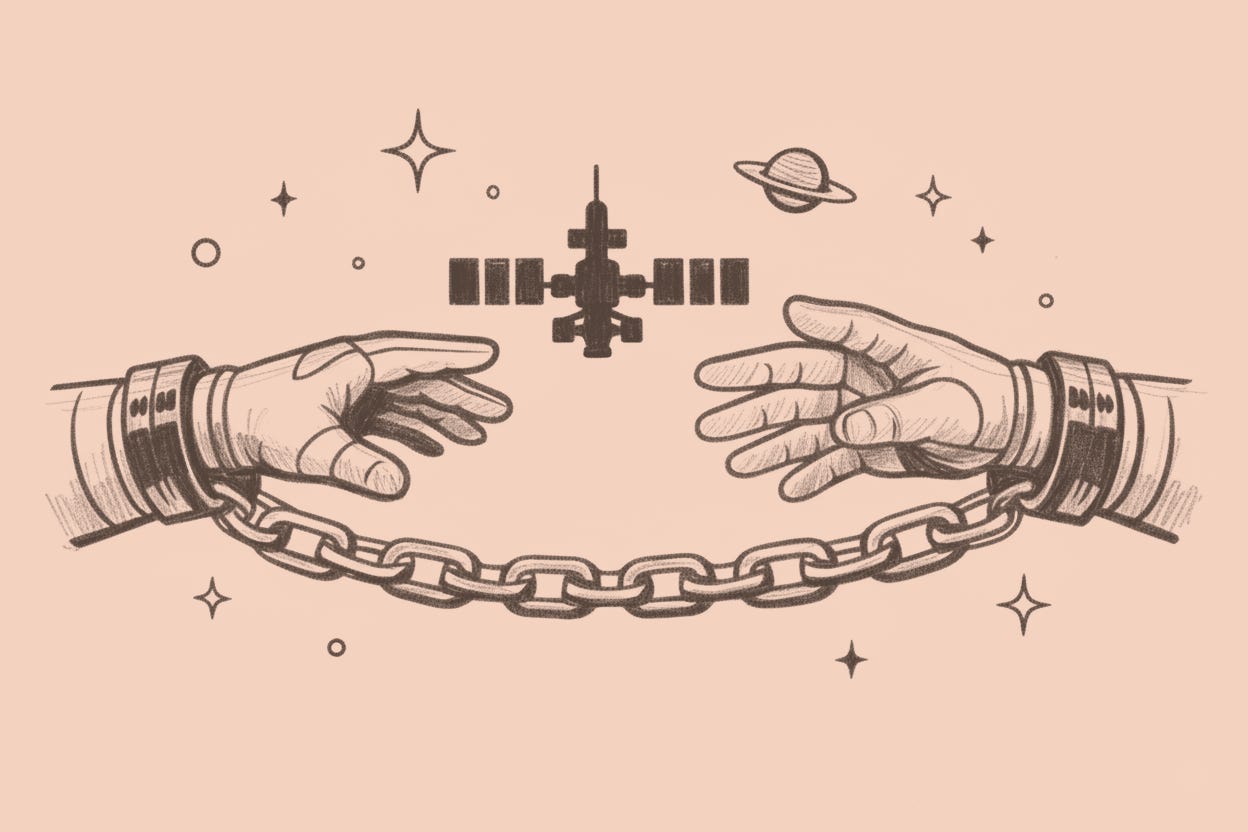

The ISS Paradox

What twenty-five years of forced cooperation reveals about human nature

In March 2022, while Russian tanks were rewriting Ukrainian geography, Dmitry Rogozin was performing a different kind of invasion: one of social media timelines. The head of Russia’s space agency had apparently decided his job description had changed from “coordinate international space operations” to “generate engagement metrics through increasingly un…