The Museum Séance

When Archive Becomes Afterlife

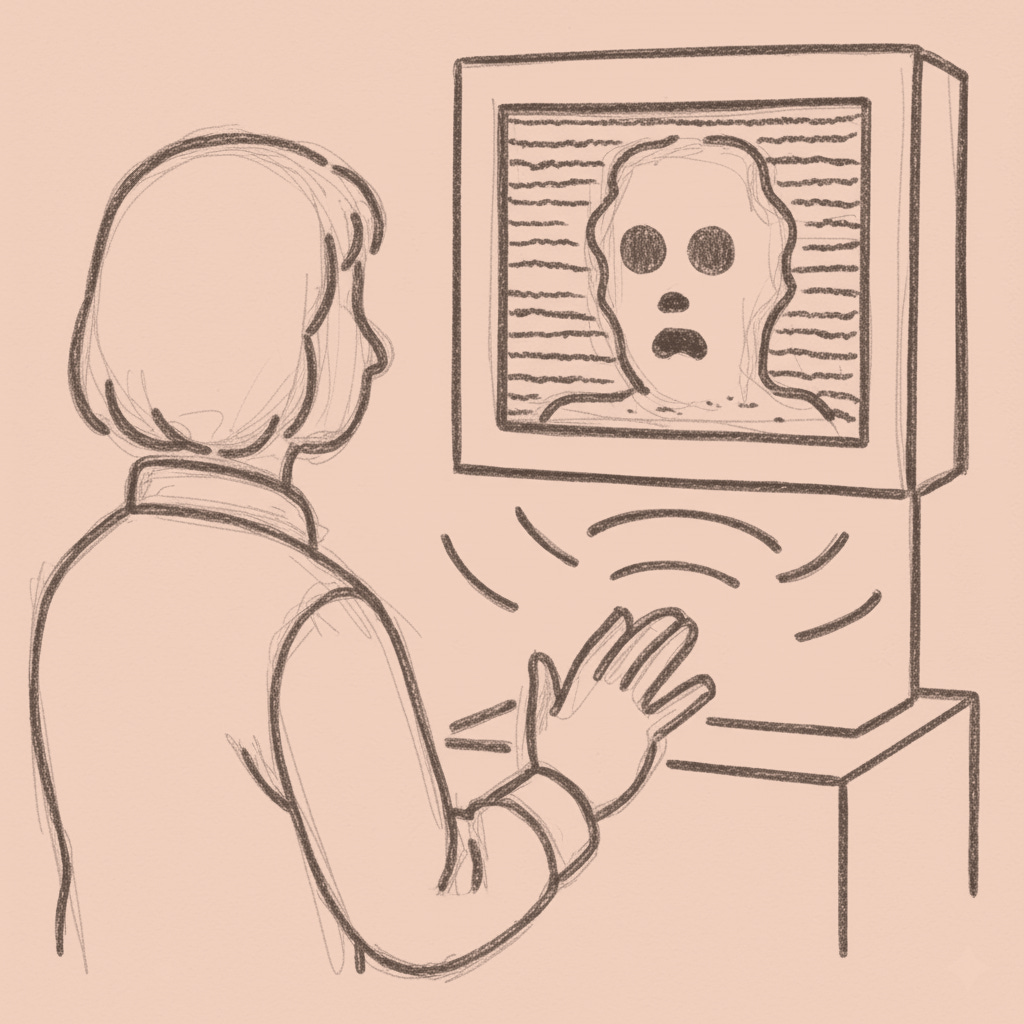

The console asks which corpse you’d like to interrogate today. The screen resurrects someone dead before your birth, their face frozen in digital purgatory. Your question hangs for twenty seconds while the algorithm rummages through a thousand ghost recordings. Then the dead person’s lips move, and you pretend this isn’t necromancy with better UX.

The mu…