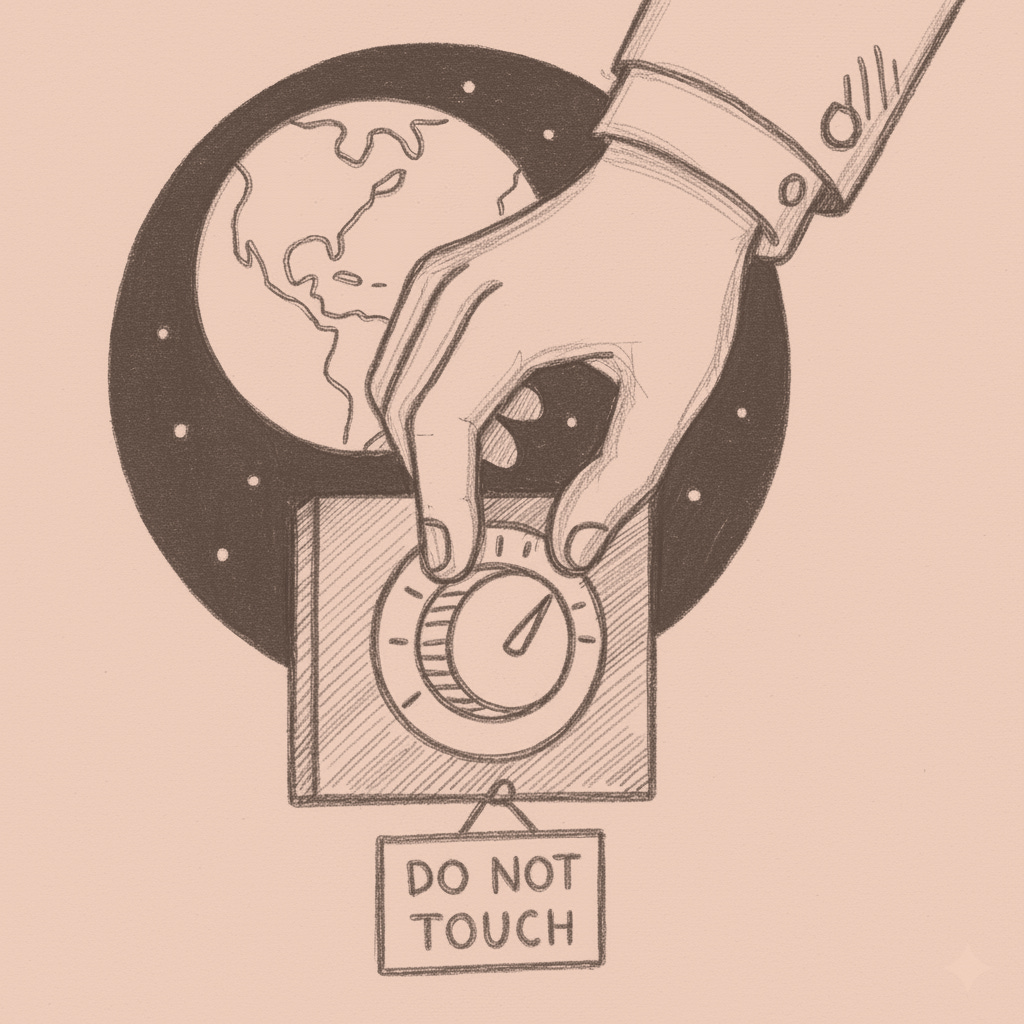

The Thermostat We're Building

How geoengineering research becomes deployment capability while we promise it never will

We’re building a planetary thermostat while promising never to adjust the temperature. This is geoengineering in 2025: fund the research, run the models, launch weather balloons carrying sulfur into the stratosphere, but call it “understanding risks” not “preparing for deployment.” The UK government says it is “not in favour of using solar radiation man…