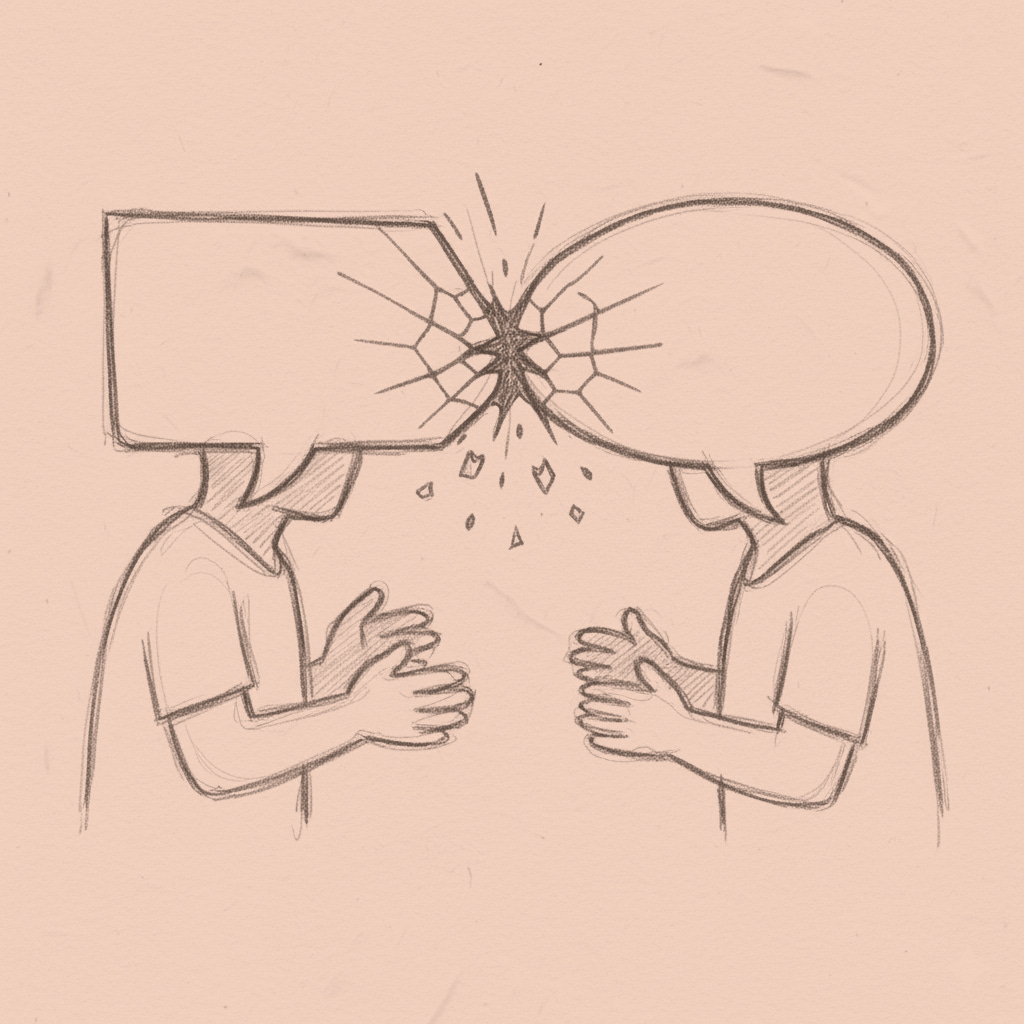

Translation as Collision

Real-time translation reveals the disagreements language was hiding

During a demo of Meta’s real-time translation glasses, a Spanish speaker dropped the phrase no manches (”no way!”). The AI faithfully rendered it as “no stain.”

The algorithm worked perfectly. It just failed to matter. It saw the vocabulary perfectly and missed the point entirely. This isn’t a glitch. It’s a preview of what happens when you optimize for …