When Augmentation Works

What AI collaboration reveals about the preferences we didn't know we had

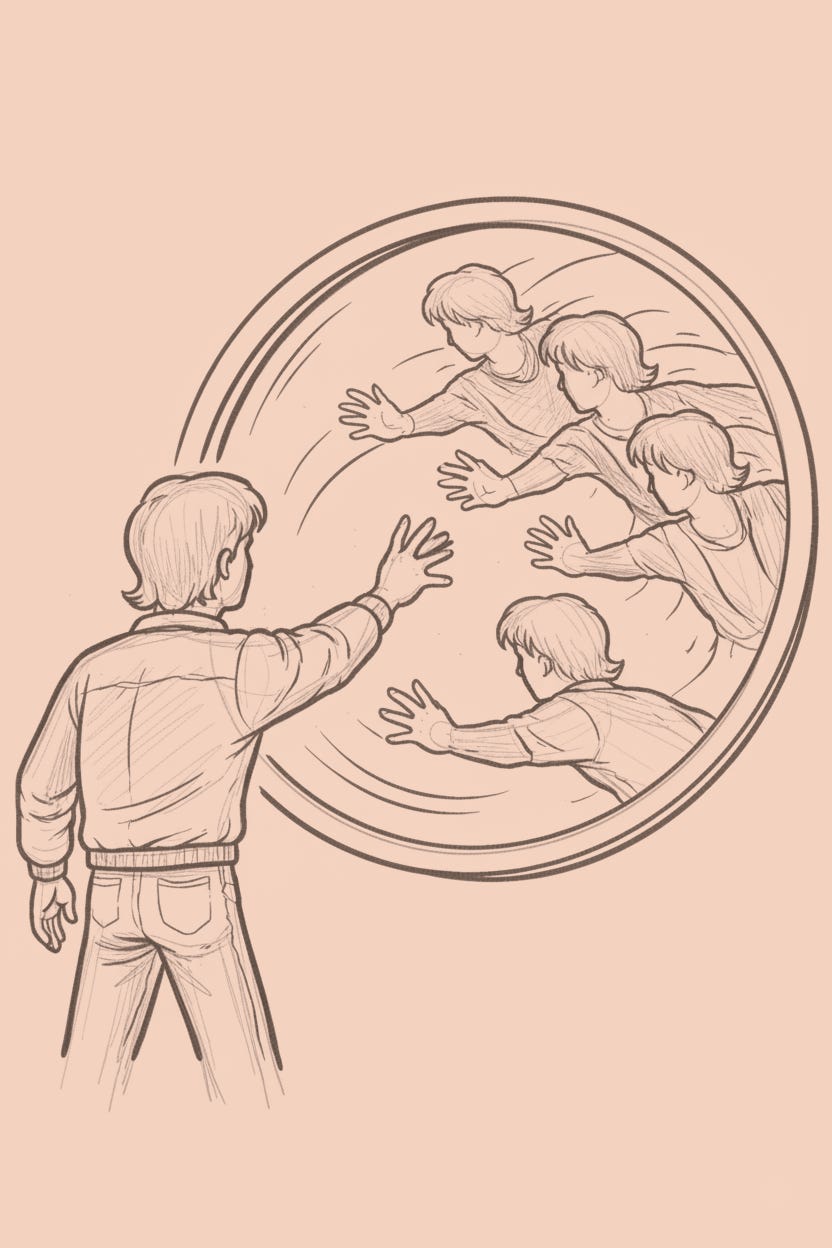

Holly Herndon calls Spawn her baby. She trained the AI on her voice, then invited it to perform alongside her. Not outsourcing creative labor: parenthood. “We chose the baby metaphor,” she explained, “because nascent technology takes an entire community to raise.”

We’ve normalized calling neural networks “babies” now. Not kittens. Not assistants. Babies.…