When Nanoscale Miracles Meet the Meter Scale

The Long Commercial Road for Graphene and Other Wonder Materials

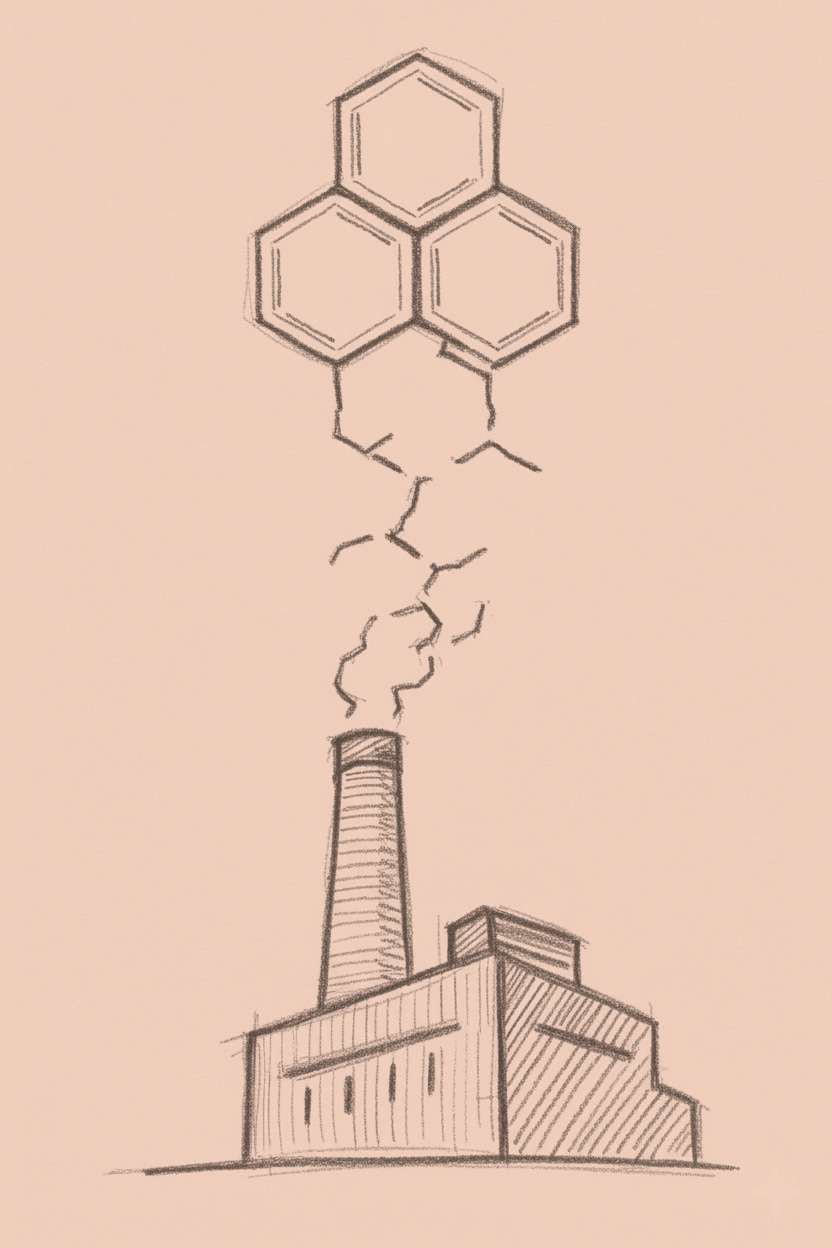

We pray for miracles. We get materials instead. One atom thick, stronger than steel, world-changing. The superlatives arrive first, the applications later, the explanations for why they never arrive at all. Graphene promised to rewrite physics and industry simultaneously. Now it’s in cement additives and specialty sensors. We’ve learned to call this pro…